How Do You Write About Books?

25 January 2021

(or, what the name of this blog is inspired by)

No, seriously. Properly expressing my thoughts about books seems like one of the most daunting tasks in the universe right now.

Now that I’ve made a safe landing from an undergraduate university program with a literature degree in all but name, writing about literally every book I come across should be a piece of cake, right? It’s just another essay JW, 95% of everything you read now is something you chose out of self-interest, so caring about the topic at hand shouldn’t be a problem anymore! All you’ve gotta do is tie in what you know about storytelling and whatever socioeconomic subjects the book deals with into how it feels to read!

Okay, but, like, how? According to my Goodreads™ 2020 Year in Books list, 3/4ths of my reading diet is made of modern adult fantasy novels, many of them engaging with topics I probably won’t ever develop my own understanding of! Heck, thinking about the last book I finished, The Once and Future Witches by Alix E. Harrow deals with the womens’ rights movements of 19th century America, the reclamation of power erased by the patriarchal forces driving history, and the fraught yet tenacious bonds of sisterhood, whether by blood or community; all framed through prose that reads like a wizened witch trying to capture the feeling of encountering magic for the first time.

…alright, nutshell summaries are a start. Writing that out feels like it took a few minutes more than it really should have—as someone who wants to tell stories like these, trying to convey how I feel about these things feels more like trudging through mud more than anything I’ve had an interest in writing about.

Though, considering what those subjects were, it’s probably not hard to see why I’m having so much trouble.

I don’t consider myself to be much of a critic. If there’s anything I’d want to peg myself, it’d be “some dude who doesn’t want to be a critic as much as they want to be critical of the stuff they love despite seeming like one to the average person in the spaces he lingers around.” Even limited to just the things I vibe with, it’s usually only after the fact when I put on my critical lens, since the works that pull me in usually end up turning off the is this good or bad and why? part of my brain in the moment. Still, as someone who reads a healthy diet of writing from internet critics, I admire the roles they play in their respective spaces—even if I harbor a niggling fear of their incisive eyes being turned upon me. (but who doesn’t, really?)

Actually, the more I think about what it takes to be considered a good critic of something, the more mind-boggling the ordeal seems To quote my favorite video essayist, Jacob Geller: “the best art criticism…[shows] art in context and in conversation with the world around it. […] To restrict yourself to the game’s text and text alone, to refuse to interact with the world that it was molded, formed, and consumed in, that is what limits us.” Taken with my understanding then, a good critic needs a constantly-growing/near-encyclopedic knowledge about their chosen subject’s canon, along with some knowledge of the canons adjacent to it, not to mention the ability to drop and defend fully developed opinions about everything at the drop of a hat.

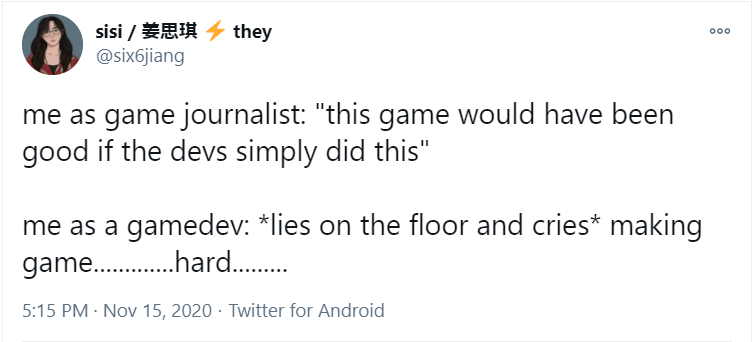

At least, y’know, that’s probably how it looks to the average viewer on social media. Heck, career critics nowadays are practically forced to have some sort of presence on social media if they want to find a stable audience for their work, and that comes with its own compulsion to have a take about even the most petty of topics sweeping through their spaces.

Can you imagine, being a critic for videogames? Bizzare amalgamations of movies, music, computer science, and a half-dozen plus other mediums, each with canons of their own stretching back decades or much longer, along with the ever-expanding annals of games’ own unique language, baggage, controversies; most of it tightly gripped to the overseers of their creation through the black box of nondisclosure agreements? Is it even possible to have a comprehensive knowledge of a specific genre in videogames, when even the smallest art experiment on itch.io that even vaguely falls under one is probably influenced by some other obscure subgenre or an isolated point of history?

Well, of course not! The point of a canon is to build a collective language for discussing a topic, a base for future explorers to chart their expeditions from. Without canons, any sort of conversation that could drive forward understanding of a topic would be as pointless as the ceaseless cacophony shouting into the void of social media.

But then again, until recently, the idea of a “canon” hasn’t really had any value to me in the first place.

In my experience, literature classes don’t teach you how to read and write analytically as much as they beat into your brain a routine for passing your assignments.

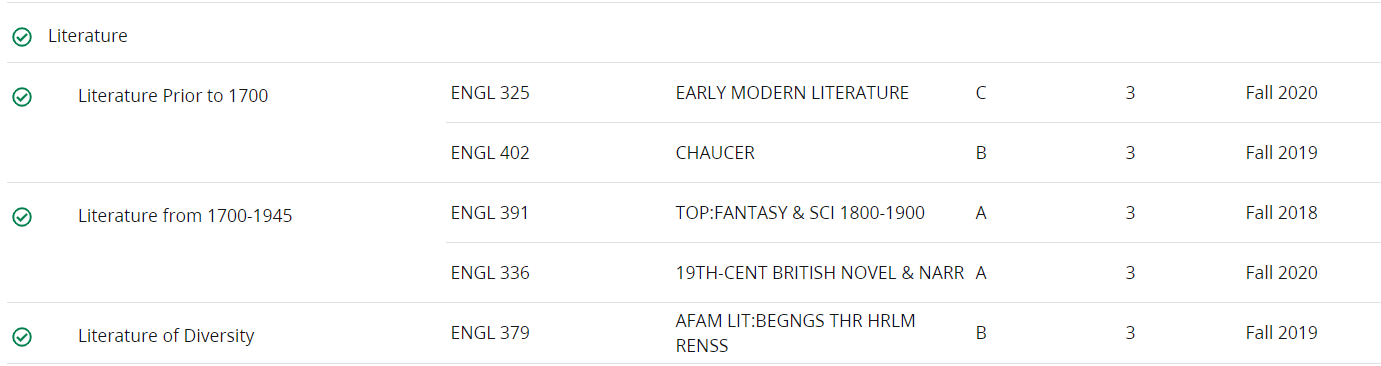

My college experience wasn’t all that great for a lot of reasons, but one of the bigger reasons was how I didn’t mesh particularly well with my chosen degree program. By the time I’d transferred to a big university I knew for sure my newly-remembered love for reading and writing would be a staple in my life from then on—so an English degree would be perfect to support that, right? If only.

The screenie of my dormant Animal Crossing avatar on the about page might be a little ambiguous, so here’s some clarification: I’m African American, though I’m so disconnected from the culture of blackness that most people would ever know unless I told them otherwise (this isn’t necessarily a bad thing). Most the centuries-entrenched “literary” canon was met with a nigh-impassible of wall in impasse: “if all these works are written from the perspective of crusty old white dudes, then what the fuck does any of this matter to me in the 21st century?”

(and these are just the classes I actually passed)

In some ways, this is a terribly shortsighted mindset. Even if most of my curriculum were works that came from an inherently colonialist, racist, sexist, and anti-queer lineage, that doesn’t suddenly drain them of any and all reasons to engage with them, especially since it would help with the works that did matter to me. But again, going by the bulk of my classes—if most of them applied to, say, studying how a the early version of a language gradually took root to become the communicative method for a modern imperialist empire, over how the rhetoric of the modern language is exponentially shrinking as the entirety of culture moves onto the internet—what was I getting out of engaging with the former outside of getting a good grade to pass the class? Why should I care, when it doesn’t speak anything to how this language is being used now?

Despite my indifference, I have the uncanny ability to use procrastination’s galvanization to produce essays that academic folks like within tiny timeframes. Doing well in school, then, wasn’t a matter of enjoying my classes, instead simply following a specific formula.

For example, here’s my procedure for a standard essay assignment: check the book’s list of prompts. Pick the one that would be easiest to write about. Read the ebook version to get through it faster—but don’t bother with the text’s overall meaning, just highlight anything that might even vaguely relate to your topic. Finished the book, but don’t remember anything that happened? Go and check Sparknotes or any other online study haven, they’ll give you refreshers while conveniently spoonfeeding you commonly held takeaways of the book’s subtext. Look over your highlights, pick out all the useful quotes, tie ‘em all together with some basic thematic analysis—boom bang pow, and JW’s got himself at least a B-worthy essay!

Of course, as someone who wrote at least a half-dozen essays per semester along with their own personal interests adding a novella’s worth of words to their overall load, honing my process to a reliable point was necessary. Yet with all my cynicism about the “literary” curriculum, what about the folks who have to write maybe two or three essays a year? Or even when we were all kids in primary school, introduced to the concept of deeper readings of books and other media for the first time?

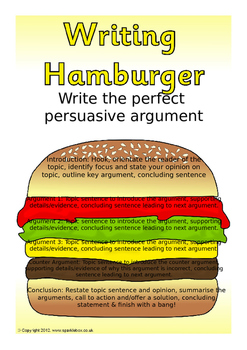

For those who grew up in American public school: remember the persuasive hamburger? If you want to write the perfect paragraph, all you need are these simple ingredients: topic sentence as the top bun, a few supporting sentences for the meat and toppings, and the concluding bottom bun. Make five of those burgers, and you’ve got a full meal of an essay. You’re free to deviate from the recipe a little if you want, sure—but since this is something you’re doing in a restaurant instead of your own kitchen, you might just get punished.

Barely any reason to take the risk, then. No writing about anything that speaks to your lived experience, no attempting to place older texts in a current context, no trying to have a conversation that wasn’t already had. Just pick the right quotes, slot everything into the formula, and get your letter grade.

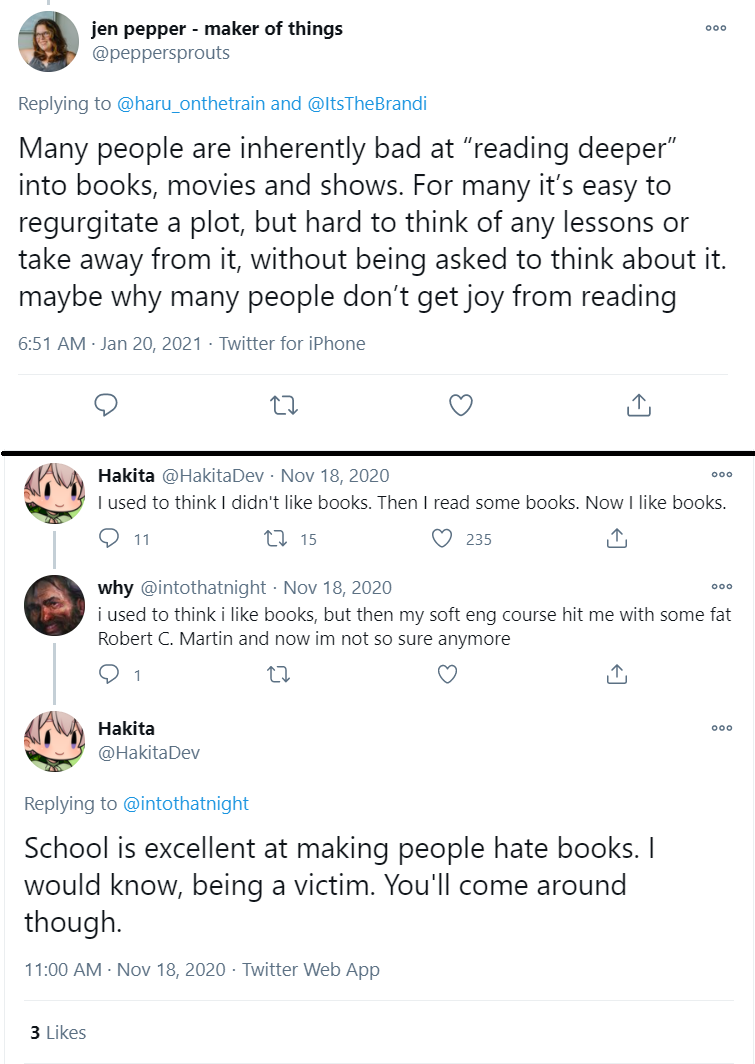

Be around the internet long enough, and you’ll probably run into the “X generation is resulting in the death of media literacy and/or critical analysis!” sentiment one way or another. And while you’ll see how I’m inclined to agree somewhat, I can’t help wondering: if the methods being taught are limited to such a systemic, mind-numbingly boring fashion, why would anyone even want to read deeper into the media they engage with for fun?

(obviously there’s a greater discussion to be had about the systems of American education here but I dunno if I’m the guy to come to it for)

Alright then, if writing about books like I did in school is a no-go, what now?

Well if my stock-and-trade is in speculative fiction, just do what you always do when you want to write in a new style: go and see how established folks talk about it and osmose their writing!

Let’s see…okay, so first, you usually start with a brief setup of a narrative or historical influences, but since that’s kinda boring you can kick things off with a quick summary encapsulating your feelings about the whole thing…then move onto focusing on all its building blocks, the characters and worldbuilding and plot, usually by picking out commonly held tropes and/or techniques and how it tries to bend them…after you’ve done that, move onto the feeling of actually reading the book…then tie it all together with a conclusion saying something along the lines of “if you’re Y feeling about X genre/storytelling technique(s)/similar book/whatever, then you’ll Z feeling your time with it…”

…huh, this seems pretty easy. Feels like I’ve done this before…at least there’s no added web of mechanics and audiovisual fidelities and whatnot on top of the plot as well…

(no you can't read them)

…hey, wait, this is too familiar, isn’t it? Didn’t you say you A) wanted to be a decent critic which involves putting the book in conversation with its surroundings, and B) never wanted to write anything that reads too much like your average consumer-focused videogame review ever again?

Now, I absolutely do not want to punch down on speculative fiction book reviewers too much with this comparison. The fact that your average review even bothers to give a book’s sociopolitical influences more than a cursory glance and that the audience for these reviews agree that this is a good thing puts them light years ahead in terms of overall literacy. It’s just whenever I do read something that sounds like a consumer-focused game review, I’m reminded of what I’m trying to leave behind.

Something I’ve come to resent about mainstream videogame fandom is how much of an all-consuming black hole it is, and how I’ve been caught in its pull for most of my life.

I’m not sure when this process began, really. There wasn’t any pivotal moment of coming to the realization that “hey, maybe there’s better things to do with your life than fixating on these things all the time,” as much as it was a gradual decline, beginning shortly after I transferred to university.

In my second semester Workplace Writing class (hi professor!), one of the assignments was to take what credentials we had at that point and craft a resume-cover letter combo tailored towards an actual job listing. Since I was unsure if I wanted to turn any of my creative pursuits into a career (currently the answer to that question outside of a chance success is a resounding nope), one of the ways I thought I could synthesize my writing with my still-favorite pastime was trying to break into games journalism (nonononononono). Polygon had been looking for an editorial intern at the time, and while I don’t remember the specifics, I definitely remember a requirement flat out stating a good applicant should have genuine interests outside of videogames.

Without any writing samples or much of any outgoing interests, I didn’t apply for the internship, but that first brush with games writing turned out to be pretty engrossing nonetheless. To make a long and meandering story short, after stumbling across and noodling around in the community surrounding VICE Games (then with the much better name of Waypoint), a decidedly left-wing political games publication, I started trying to find deeper meanings to things, to reorient myself away from videogames and more towards the world around me. The blinders on my eyes gradually came off—and most of the friendships I’d built up to that point began to seem shallow and flaky.

As I've chipped away at my current project, I’ve done a fair bit of reading about the dynamics of mainstream internet fan culture. Even if you don’t dive into the weeds of specific incidents, seeing the direction fandoms have taken the greater media landscape doesn’t bode well for the future: how critiquing a fandom’s product of choice is equated to a personal attack, how art produced by big corporations is being shaped to satisfy them, and how responses to those critiques can quickly become toxic harassment campaigns.

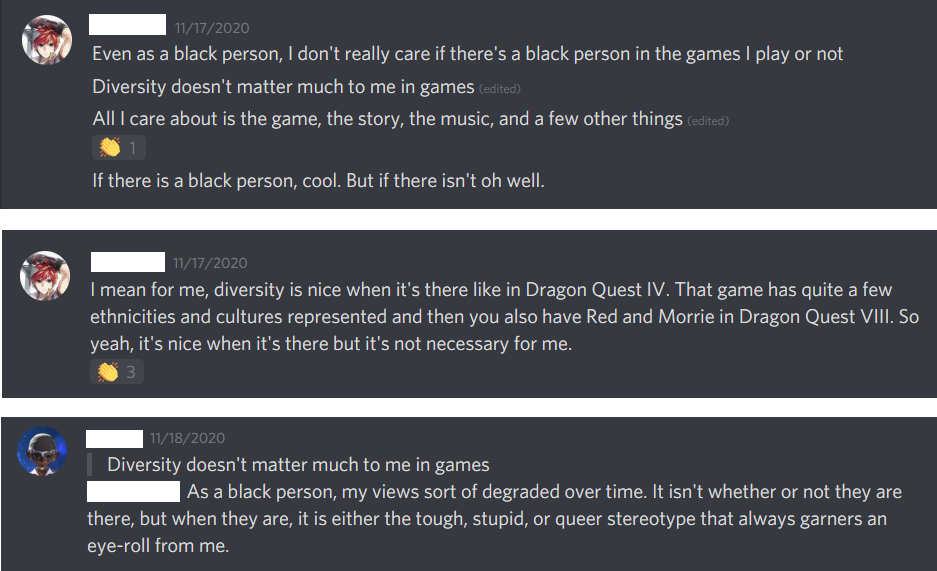

It’s a sad unreality we live in around. A very good end-of-the-decade blog by ellaguro chalks today’s fan culture up as a result of the world’s existential problems, including the lack of media literacy within a 24/7 deluge as all culture is shoehorned onto privatized social media platforms, the commodification of marginalized conflicts by corporate art, and the neverending obsession with the present without any awareness of the past, among many other things. You’d probably think that folks who only linger in or outside the periphery of fandoms (mostly non-marginalized folks who don’t need their existence to be validated when the systems they live in don’t and can reliably keep their lives away from online spaces, I think?) would be better off. With these tsunamis of fanatical devotion washing over the entire media landscape though, these dynamics are undoubtedly trickling down into how far-removed people talk about their favorite media, including the spaces I mingled in.

I was (and mostly still am) a pretty awkward dude in person; disconnected as I was from everything when I transferred to a big university, I mostly found myself around other awkward and disconnected dudes as well. Of course, we all “connected” around videogames, and I got plenty of laughs from messing around near the university’s fighting game scene as well, so things weren’t too bad, all things considered.

When the bedrock of everyone’s identity is based on pop culture though, trying to move away from that only made me seem more awkward in comparison. Whenever I mentioned how school took precedence over hanging out for me, or what cool indie game I had just played, or tried to add nuance to a conversation against a complaint about why X game was like it is, or my creative projects—or even Dragon Quest when it actually got a foothold in the cultural consciousness with all the Nintendo hype—I was met with idle reactions, if I got anything at all.

Nobody was really there for any genuine connection, it seemed—certainly not as much as who can I whale on in Smash Bros to inflate my own ego, or how many memes can I reference about whatever zeitgeist videogame or YouTube video to look cool? As far as they were concerned, college and the rest of life was just an obstruction from their favorite fixation.

Both of the first posts I wrote on this blog have parts that wouldn’t seem that out of place on your average videogames site, that incredibly enthusiastic tone a stone’s throw away from a declaration of “whoa this is the best thing ever and you gotta play it cuz you’re missing out if you don’t!!!” I don’t necessarily mind writing in this tone, since I probably end up sounding like that to most folks in person, but there’s still all that leftover baggage. No wonder I didn’t see any value to canons before—if nearly everything my existence was oriented around was made to be so removed from history, why would I think trying to understand it would be meaningful?

I told myself I wouldn’t write about this ‘till I’m much further along with it because of how my turbulent sentiments about the original game still haven’t settled. But, it’s also kind of the crux of this entire post (and maybe even a case of practicing what I’m preaching since I’ve made hints towards it before), so…

hi! I wrote half of a love letter to #DragonQuestXI, which is, incidentally, a personality-extending/world-detailing/mechanical-melding/romantic(?)retelling fanfic centered around my two favorite characters, Erik & Serena. #Serenerik #カミュセニャ #DQXIhttps://t.co/ls08jD7y2Z pic.twitter.com/gudAFpwzBE

— JW (@jwhighwind) January 11, 2021

Over the past year and some change, I’ve been writing a retelling of Dragon Quest XI: Echoes of an Elusive Age, the latest major entry in a series that can summed up as “Disney-esque fairy tale JRPGs but Dragon Ball.” As the series that codified the blueprint for the genre we all know and love and/or loathe today, Dragon Quest has been an immense cultural object in Japan since the release of Dragon Quest III in 1988, enough that it's slated to get a theme park attraction this year. With that entrenched relevance, the series hasn't moved much more than a few centimeters from its classical roots of turn-based combat and simplistic stories centered around silent heroes undertaking a journey to save the world from cartoonishly evil villains. It’s probably the most conservative videogame franchise ever, churning out comfort food for the entirety of its 35-year existence—but goddammit, is it some tasty comfort food. At least on the first go around.

The Healer and the Vagabond, my fanfiction in question…probably looks like comfort food, but is really a messy collection of hard-to-swallow pills. I frame it to most people as a romantic retelling centered between Erik, the pretty popular aloof thief (and “partner” of the main protagonist), and Serena, the definitely-not-as-popular softhearted healer of the main cast. The further along I get with writing it, the more this becomes a horribly reductive summary.

I call it a love letter, but when I say “love” I mean it in a specific, critical way—because in a lot of ways, it’s a rejection of the ideologies of both the original work and the culture it was born within. All your AO3 staple hurt/comfort and angst and pining and fluffy bits and what have you are there; but instead of your typical holding hands or kissing or impassioned mutual confessions, the payoffs are Erik and Serena coming to terms with themselves. (those moments do happen, but most are either made to be subverted or played for kicks, lmao)

While their original arcs and rest of the main cast can easily be considered the best in the series, it’s fairly easy to make the argument that both Erik and Serena’s are paltry hand-waves, so the entire retelling is devoted to giving the thematic parallels between them as much depth as possible. In this way, it’s also a keenly personal tale. Fairy tale aesthetics aside, much of their personal tensions align pretty closely to my own childhood, making it a retrospective outlet for my own—not necessarily by self-inserting, but their extended personalities (and all but one of the characters highlighted in the tags) carry a piece of it, in a sense.

It starts out following DQXI’s story from their perspectives pretty closely, but the further it goes along, the more the hero’s journey becomes background noise. Once it hits the second act of the story proper, where Serena and Erik and the rest of the hero’s friends are separated in a ruined world, the gloves come off for me to dig into the moral conundrum hidden behind the game’s mechanics and narrative framing: Dragon Quest XI is a game that tells a story about love where the player’s primary method of engaging with its world is violence carried out against monsters that have become increasingly humanized as the series goes on.

(yes, there's a French boarding school in this game and yes, the retelling is here for like a quarter of its runtime so far)

Most of the time, I’m reluctant to call it a “fanfic” or even just a “story,” because it’s so many things. For better or worse, it’s my first longform piece of fiction. In some ways, it’s an affirmation, as I take these characters that, (to me) barely seem to exist in their world and showing how it molded them; but soon, it will become a condemnation. It’s a response to a game that, despite its intentions, has managed to give me so much. Whether it will be a farewell or not remains to be seen.

Anyway, I need a place to vent this out before it burns a hole in my brain, so here’s a full disclosure of a rant:

(click to reveal)

I think the hero is one of (if not the) worst parts of Dragon Quest XI, which is also the reason I’ve been fixated on the roles of silent protagonists in videogames for a while now. The overwhelming majority of DQXI’s fandom sentimental enough to ship characters thinks Erik should be with the hero because of the “bond” between them. While I’ll admit that these critiques were absolutely petty jealousy at first, at this point it’s much more due to how this doesn’t hold up at a higher mechanical level (in a genre where the fun comes from minimizing moment-to-moment randomness as much as possible, most of their “synergy” comes from a flashy limit break system that the player has very little control over until they’ve completed the main storyline after at least 50~60 hours) or narratively (there’s not much difference between the loyalty Erik and the other party members profess to the hero—he was just the first, and speaks up for them the most, because, y’know, they aren’t supposed to).

DQXI’s devotion to aggrandizing the player character and the series’ legacy along with its refusal to interrogate itself (despite a handful of scenes—including a couple where the hero actually speaks for himself as a child—setting this up) bleeds out what depth its story could’ve had. But, as important as I think it is to point this out because of how much space Dragon Quest eats up in the genre, it wasn’t ever made to tell nuanced stories or be much more than a series of self-insert power fantasies in the first place, so ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

(most people think it can go either way for Erik because of postgame shenanigans and everyone in the party is playersexual anyway, so obviously the solution is just for everyone to embrace polyamory between the hero and Erik and Serena—but shipping anyone who isn’t the girl next door who knew the actual person with the half-baked potato you get to play as? Get outta here)

My opinions about DQXI are about a million times as complex as the actual game itself; since properly writing about it would involve discussing the dynamics of fandom, the community surrounding Dragon Quest, my own engagement with both over the past three years, and Yggdrasil knows how much else. So, instead of furthering ideas for the inevitable essay, I’ll leave you with two diametrically opposed reviews around the original English release in 2018: Kotaku’s glowing one from the infamously verbose Tim Rogers, and Cameron Kunzleman’s critical skepticism over at VICE Games.

The art of storytelling with the written word predates videogames by literal millennia. In a distantly modern context, the earliest form of the English novels we read today are still older by 500 years. As it relates to me today, many of my favorite authors weren’t considered good enough to get published until they were at least in their 30s, after a long, rejection-filled road with countless scrapped stories left by the wayside.

Since The Healer and the Vagabond was originally intended to be a “fun little distraction," I decided I wouldn’t learn any specific writing techniques unless absolutely necessary; so when I eventually finish, I can pick out the weakest links and work up from there. I’m simply someone stumbling along as best I can with what relatively little I’ve osmosed over the years. This…thing isn’t just some story, its a piece of my soul made manifest in text, something nobody can take away from anyone. And while I’m sure the more works a writer makes the more things might gain a degree of remove from themselves, I think the solitude inherent in the pursuit never diminishes how personal it is.

How the hell can I have the audacity to critique something anyone else writes outside of a “I liked it/didn’t like it” capacity? How can I have the authority to say whether anything is good or true to life or not, if I can’t even touch on the supposed process of it’s creation, or even know what part of life it’s pulling from?

These…aren’t really questions anyone can definitively answer, I think. They’re mostly just a confluence of the need to sound authorative to get anything across to people on the internet, and the humility that comes with being a creator, plus my typical pseudo-philosophical pondering.

If anything, I’d say my writing style is probably a tad too adherent to the conventions of the games-writing-sphere it came from, so I’m gonna try to embrace those nutshell summaries for writing about other things. I want to start making shorter posts about more kinds of media I’m messing around with in all kinds of genres (and I’m not kidding), but I’ll probably settle with just books for now. I’ve been slowly getting back the regular reading part of myself that fled even further away with 2020's events plus the online-school-stress combo, so depending on how many thoughts I can gather together there’ll be one every month or so. Maybe. Probably.